Critical Minerals for a Clean Energy Transition

Mitch Juneau, PhD, Fellow

November 2022

Introduction

The term “clean energy transition” is likely one you’re familiar with given the recent windfall of climate-related legislation from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill – both of which were signed into law in the last year. These bills provide over $500 billion in tax credits, loan guarantees and other incentives, hoping to spur clean energy innovation from R&D to demonstration. However, investments in clean energy are not limited to the public sector. The private sector is also investing heavily in clean-energy startups with approximately $70 billion invested over the past two years.[1] Public figures like Bill Gates have remarked that recent innovation is accelerating “faster than {he} dared hope.”

Artist’s rendering of Apex 1, Ascend Elements’ new 500,000 square foot, sustainable lithium-ion battery material facility in Hopkinsville, Kentucky. Image Source

Recent cost reductions in solar photovoltaics (PVs), wind turbines and electric vehicles (EVs) have further enabled this energy transition away from fossil-based systems as more than a third of publicly traded private companies have launched net-zero targets.

However, a shift away from traditional hydrocarbon resources is far from a drop-in exchange and comes with its share of challenges. A primary one arises in the supply chain of critical minerals required to enable the development and deployment of these technologies. For example, a typical electric car demands six times the mineral requirements when compared to a conventional car with an internal combustion engine,[2] and onshore wind requires nine times the mineral inputs per megawatt produced compared to a natural gas plant.[3] Beyond the increased need for critical mineral components, many of these mineral requirements are widely varied beyond established fossil fuel supply chains and subject to price volatility due to demand swings and geopolitics.

Revolutionary changes to our systems of energy production and electrification of our day-to-day life could lead to an almost unrecognizable world of abundant clean energy. The potential for this fantastical future inspired our topic of discussion, which I’ve informally named after the Wizarding World of Harry Potter, Critical Minerals and Where to Find Them.

List of Key Minerals & Sourcing

A global clean energy transition will likely encompass wide-ranging technologies from solar PV and wind electricity production to EVs, battery storage and future hydrogen production. This list of technologies is varied and constantly evolving, and consequently projections of the type and volume of mineral needs vary widely. However low-carbon technologies like EVs and renewables generally rely on the same five key minerals or mineral categories which will likely direct rollout. Supply bottlenecks and environmental impacts of production will likely play a key role in the cost and adoption of differing energy solutions.

These core five minerals needed for clean energy technologies are: Lithium, Cobalt, Nickel, Copper, and Rare-Earth Elements (REEs).

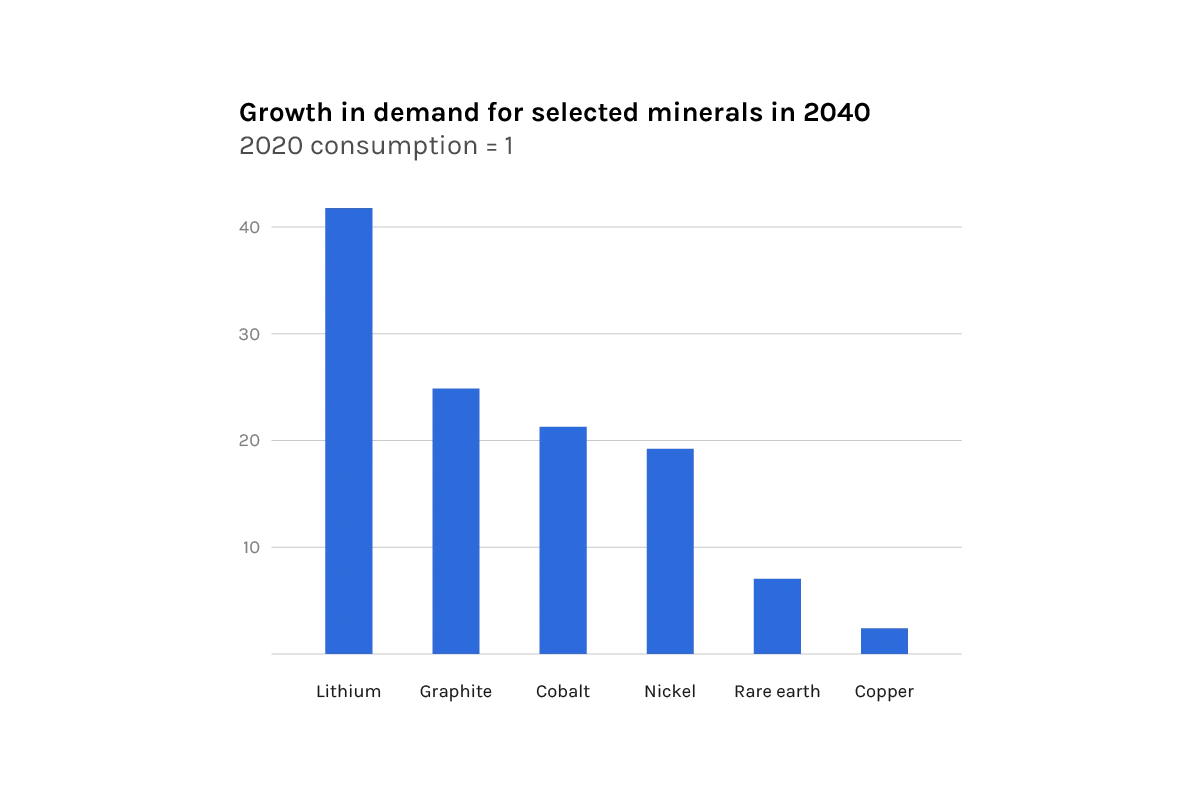

Each of these critical minerals are sourced in a different fashion with geopolitics influencing current global sourcing, but can largely be broken down into the countries who mine or produce these minerals, and the countries that process them. For example, a case study can be performed on electric vehicles, which have been estimated to account for 45% of new cars in 2035,[4] and up to 66 million cars total in 2040.[5] The production of one electric vehicle requires a wide array of mineral resources – approximately 66 kg of graphite, 53 kg of copper, 40 kg of nickel, 25 kg of manganese, 13 kg of cobalt, 9 kg of lithium, and half of a kilogram of REEs. If you extrapolate these mineral requirements by the expected number of deployed EVs ignoring all other energy technologies, this can result in an increase in mineral demand from 15 to 43 times the current 2020 demand by 2040. The average mining development project takes anywhere from 4 to 16 years to just open an ore deposit for production, making it difficult to meet near-term expected demand. While new mining projects are still essential, it becomes clear that technologies enabling increased production from current mines and recycling minerals from deployed technologies will be critical in addressing the explosion of demand that comes with a global clean energy transition.

When one thinks of energy storage or electric vehicles, lithium comes to mind as a core component of these technologies and reigns supreme over its competitors. However, despite how ubiquitous lithium energy storage technologies have become, lithium (Li) production is concentrated in two primary source regions: South American brine ponds in Argentina and Chile, and mined spodumene in Australia, corresponding to 39% and 49% of global production in 2020 respectively. Further analysis of price fluctuations and global reserves is detailed effectively in a recent blog post. Despite these two regions’ dominant production of raw materials, processing occurs largely elsewhere with China producing almost 60% of the global lithium chemicals and over 80% of lithium hydroxide (a key precursor of Li EV batteries). Interestingly, the USGS estimates that while the US has over 750,000 metric tonnes of economically recoverable lithium, these sources are complex and expensive to extract due to the lower average concentrations of lithium as compared to South American brines. Furthermore, permitting of new domestic mining and mineral processing projects can be lengthy and complex, delaying the immediate benefits of future domestic Li supply streams. Despite this, several domestic operations are gearing up to access clay, hard rock and geothermal brine Li sources in Nevada, North Carolina and California respectively.[6] With Li demand predicted to increase by over 40 times over 2020 demand by 2040, the limited number of Li processors worldwide could result in a severe bottleneck in deployment of EV and energy storage technologies, which rely heavily on this mineral.

Electric vehicles at solar charging station. Image Source

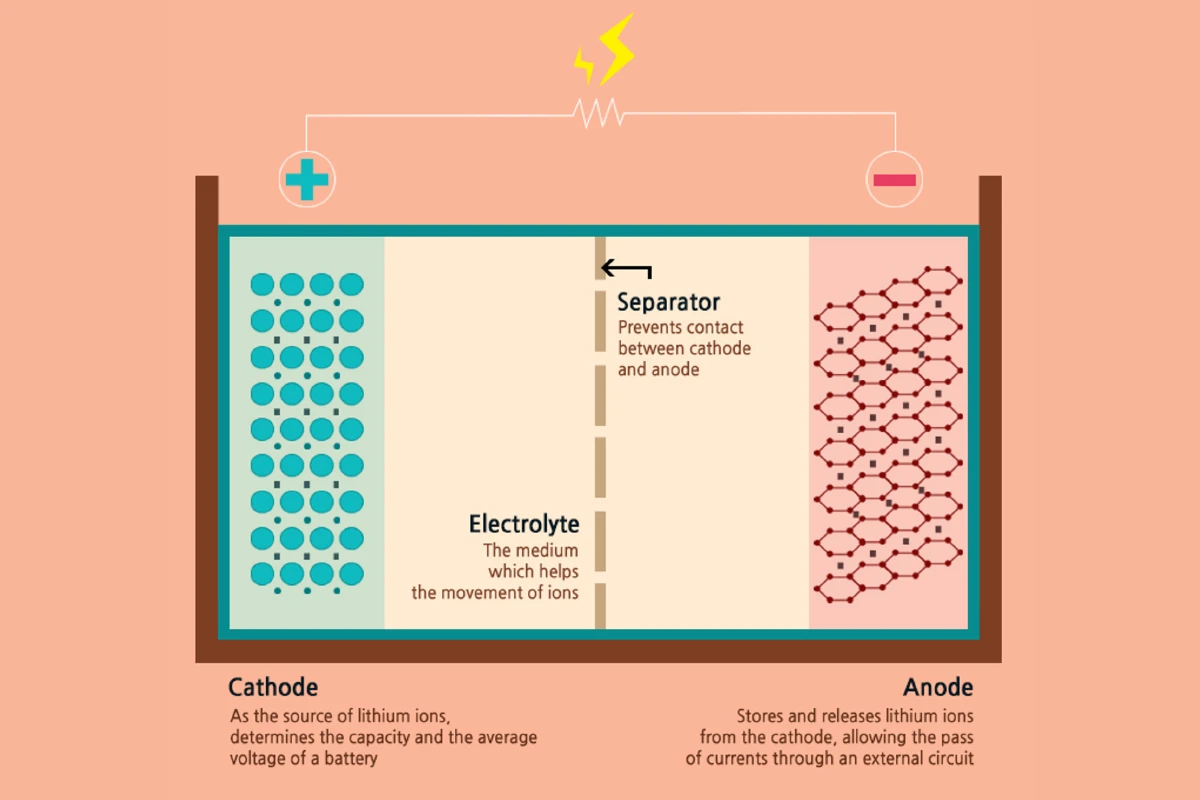

Similarly, while Li is critical as an energy transfer mechanism in current battery designs, a key driver in increased energy density in Li ion batteries is the cathode. As a quick refresher, in a fully charged battery the cathode is the source of Li ions which flow through the electrolyte to the anode, allowing an equivalent transfer of electrons to flow through the wire providing electricity. Li battery chemistries deployed in consumer electronics traditionally rely on Lithium Cobalt Oxide (LCO) for its high energy density per unit volume, however LCO batteries face drawbacks in their shorter life spans, low thermal stability and low energy density per unit weight. Electric vehicles draw more power from their batteries than consumer electronics and employ different battery cathodes traditionally using a Nickel Manganese Cobalt (NMC) cathode, whereas Tesla’s electric vehicles generally rely on a Nickel Cobalt Aluminum Oxide (NCA) chemistry. As the cathode names would suggest, for many established and proposed battery chemistries, Cobalt (Co) and Nickel (Ni) are used within their cathodes. Consequently, an increased deployment of Li ion battery technologies also requires significant sourcing of Co and Ni raw materials.

Over 70% of Cobalt (Co) is produced in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) as a byproduct of copper and nickel mining. This cobalt is then predominantly transported to China which processes around 70% of mined Co globally. Furthermore, as Co is usually produced as a mining by-product, its price is highly susceptible to market conditions of copper and nickel, which raises concerns about future supply. The IEA estimates that cobalt demand in 2040 will be 21 times greater for EV applications compared to the demand in 2020. This demand prediction further emphasizes the need to increase market-resilient supply chains of Co, rather than relying on its production through existing copper and nickel operations.

Nickel (Ni) also will play a key role in high-nickel battery cathode chemistries employed in consumer electronics and EVs. Production is largely concentrated in Indonesia and the Philippines representing 45% of global nickel production. However unlike Li and Co, where raw minerals are primarily exported for processing in China, Indonesia recently implemented a ban on nickel ore exports to promote domestic smelting and processing into refined higher-value nickel products. Additionally, the production of 1 kg of Ni metal is linked to over 13 kg of CO2 emissions[7] with severe environmental effects on local communities due to water pollution from mine tailings and air pollution from processing nickel sulfide deposits. Severe price fluctuations of Ni and Co could affect battery chemistries in future EVs as viable high-nickel and high-cobalt designs have been effectively deployed already in NCA and NMC batteries, and raw material cost will be a key factor in their competitive adoption across the industry.

Samsung’s infographic, “The Four Components of Li-ion Battery”. Image Source

While Li may be great at storing energy, Copper (Cu) is a fantastic means of transferring it, or electrons to be exact, through grid electricity transfer and numerous other electronic and industrial applications like solar PV and wind. The South American countries of Chile and Peru are the largest producers of mined copper, responsible for 40% of global output. While Chile does possess domestic Cu processing capabilities, much of Cu is exported and processed in China, Japan, and Russia. The growth in demand of Cu is expected to increase by roughly 1.5X over the next 20 years. This increase in demand is gigantic, as the 2020 global mine production of Cu is estimated at 18 million tonnes per year. This is more than 6 times greater than the estimated 2020 production of Li, Co, and Ni combined. Furthermore, the mines currently in operation are near peak production, with declining ore quality exerting pressure on production costs. More energy and resource-intensive exploration is further exacerbated by climate change-related water scarcity in dry mining regions like South America and Australia. Of all the energy minerals examined here thus far, copper production is unique in that the United State is largely self-sustaining at the current demand with 8% of global Cu production and a45% end-of-life recycling rate. However, increased production costs and increasing demand could threaten this self-sufficiency in the near future.

Rare earth elements (REEs) are a family of elements consisting of the 15 lanthanide group elements along with scandium and yttrium. REEs are used in a variety of different applications. Those primarily of interest to the clean energy sector are that of neodymium, dysprosium, praseodymium and terbium due to their inherent electronic and magnetic properties. Most electric motors in new EVs and in energy production applications like wind turbines are powered by permanent magnets made of these rare earth metals, with cross industry demand expected to increase by 6 times over the next 20 years. Currently, China is a major producer with over 60% of the production market and almost 90% market share of REE processing.

Additionally in 2010, China attempted to limit REE exports, which are crucial to the development and deployment of a wide variety of clean energy technologies. This prompted many countries to diversify their own domestic REE production capabilities. The United States specifically has been developing several new processing plants to ensure stable domestic production of this critical group of minerals, with MP Materials in Las Vegas investing over $700 million to develop a rare earths magnetics production plant set to open in late 2023. Furthermore, current processing techniques for neodymium oxide (a powerful permanent magnet REE) emits more than 62 metric tonnes of CO2 equivalent to produce one ton of REE, severely undercutting greenhouse gas emissions offset by the clean energy technologies deployed with these magnets.

Production and processing of these critical minerals is often controversial within local communities due to the environmental damage that can be wrought from mine tailings ponds leaching into local waterways coupled with greenhouse gas emissions along with other air pollutants negatively impacting surrounding areas. Production and processing of these critical minerals is primarily consolidated in a few countries with China dominating global mineral processing. However, energy security concerns in the United States and Europe have prompted governments to secure their own domestic critical mineral supply chains. Moreover, evolving responsible sourcing expectations from governments and companies in the United States and Europe coupled with pushes for domestic supply chains. Both of these trends threaten China’s mineral processing dominance in the near future, more closely examined in this report by the Brookings Institution.[8]

Meeting the expected increase in demand while dramatically changing established mineral supply chains will require retooling our established systems of production and introducing new technologies to enable strong and sustainable sources of energy minerals for our energy future.

Data Source: IEA, Growth in demand for selected minerals from clean energy technologies by scenario, 2040 relative to 2020

Mechanisms to Meet Gaps in Market

Given the recent geopolitical upheaval seen in oil and gas markets by Russia’s invasion in Ukraine, domestic production and processing of these critical minerals has come to the forefront as a priority for both economic and national security. The International Energy Agency in a recent report highlighted 3 key mechanisms to meet a potential gap in the minerals market: Diversify Sources, Promote Tech Innovation, and Scale-up Recycling.

First, to begin to address these security issues the U.S. Department of Energy has recently announced over $200 million of funding devoted for new technologies to grow the domestic critical minerals supply chain along with the development of a first-of-a-kind critical minerals refinery. However, many of these alternative mineral sources are currently untapped, with technologies to access/process these resources in their infancy, which have yet to be deployed at a national scale. One clear example of diversifying domestic mineral sources is found in a “globally significant” deposit of Co in the mountains of Idaho. This deposit has not been accessed since the Blackbird mine was shuttered in the late 1980s due to significant concentrations of toxic arsenic complicating the cobalt’s extraction and leaving contaminated water and a superfund site in its wake. Jervois, a publicly traded mining company and primary developer within the Idaho Cobalt Belt where the Blackbird mine is located, is in the process of reopening the Blackbird site, aiming to meet sustainable production in early 2023. This mined cobalt would be shipped to its Ni and Co refinery in Brazil and is expected to produce 2,000 tons of cobalt a year, meeting around 10% of expected United States demand.

Promoting technical innovation for efficient use of existing mineral streams and enabling access to new supplies is also critical to securing domestic supply chains. Several new startups are employing technologies that enable access to previously neglected sources or existing sources with higher efficiencies. One commonly overlooked source of valuable mineral resources is that of mine tailings ponds, which are engineered storage areas that capture and recycle water used in the mineral extraction process.

Scarecrow at Tailings Pond in Alberta, Canada. Image Source: National Wildlife Federation

Often thought of as an environmentally hazardous waste stream, Massachusetts start-up Phoenix Tailings sees a unique opportunity in recovering valuable resources from this waste stream. Using their patented extraction technology, Phoenix Tailings can recover REEs, Ni and Mg from mining waste, and has received recent grants from ARPA-E and DOE for their carbon neutral and carbon negative processes. We talked with the CEO of Phoenix Tailings, Nick Myers, about his perspective on current mineral extraction technologies and their vision for the future along with two leading researchers at Idaho National Laboratory and Berkeley Lab, which you can listen to here. Furthermore, many existing mineral streams can be recovered at greater efficiencies when new technology is deployed. Lilac Solutions, specifically, has raised over $150 million in late 2021, with a patented ion exchange technology to enable lithium extraction from brines eliminating the need for evaporation ponds and enabling twice the lithium recovery compared to conventional processes (80% recovery vs. 40% with evaporation ponds).

Lastly, scaling of recycling processes offers a unique opportunity in recovering value within waste streams and enabling circularity in a growing clean energy economy. End-of-life recycling is well-established with high rates of recycling for many valuable metals such as gold, platinum, palladium and silver; however these rates drop for lower cost metals like Cu and Co (46% and 32% respectively). Furthermore, existing pathways of recycling for Li and REEs are virtually nonexistent, but several start-ups within this space are looking to change this specifically for Li energy storage devices. A plethora of technologies from pyrometallurgical to hydrometallurgical to even plasma treatment are being deployed by start-ups like Redwood Materials, Li-Cycle and Princeton NuEnergy, to extract valuable cathode materials like Ni, Co and Li for processing into new recycled Li battery technologies. This is a ripe area for investment with over $1.5 billion of private investment in Redwood Materials and Li-Cycle alone and with $480 million approved by DOE for Ascend Elements to establish a manufacturing facility in Kentucky for materials separation, processing, and component manufacturing.

Lithium-ion batteries during the recycling process in Li-Cycle’s Rochester, NY plant. Image Source

Summary

To enable a global clean energy transition, the deployments of wide-ranging energy production and storage technologies require a stable and secure supply of critical minerals like Lithium, Copper, Cobalt, Nickel, and Rare Earth Elements. These minerals are currently produced at far below the levels needed in 2040, with existing operations nearing their production limits due to declining ore quality and rising extraction costs. Geopolitical risk (with over 70% of the world’s cobalt production in the DRC and over 90% of REE processing in China) and high CO2 process emissions (up to 62 kg of CO2 per one kg of neodymium produced) demand new technologies that are capable of extracting mineral resources from domestic sources, at higher efficiencies and with lower carbon footprints. Some companies are looking to open or expand US production with Jervois aiming to establish an Americas-only supply of Co within 5 years, along with domestic Li producers gearing up to address the explosive demand that comes with EV adoption. Furthermore, an increasing number of startups are developing novel, more efficient production, refining, and recycling processes enabling access of previously underutilized resources like mine tailings ponds to meet the critical mineral requirements of tomorrow. We expect to see further innovation in the years ahead as demand pressures increase.

Notes

[1] GatesNotes “The state of the energy transition” attributes 42% of global emissions are attributed to the electricity and transportation sectors, with electric vehicles and clean energy technologies posed to lower these emissions with roughly $70 billion invested into over 1,300 clean-energy startups.

[2] Electric cars require approximately 207 kilogram of critical minerals/vehicle (66.3 kg Graphite, 53.2 kg Cu, 39.9 kg Ni, 24.5 kg Mn, 13.3 kg Co, 8.9 kg Li) vs. 33.5 kg/vehicle (22.3 kg Cu, 11.2 kg Mn) in an internal combustion engine. IEA Report

[3] Onshore wind production requires about 10,153 kg/Megawatt produced (5,500 kg Zn, 2900 kg Cu, 780 kg Mn, 470 kg Cr, 404 kg Ni, 99 kg Mo) vs. 1,148 kilogram per Megawatt produced in a natural gas plant (1,100 kg Cu, 48 kg Cu). IEA Report

[4] Reuters Graphic “The long road to electric cars” references paths forward to adoption of EVs from less than 1% of the current fleet being electric to expected 45% deployment by 2035 according to industry analysis from IHS Markit.

[5] Bloomberg Market post citing “At least two-thirds of global car sales will be electric by 2040”.

[6] Thacker Pass, Nevada is currently the largest lithium resource being developed by Lithium Americas, estimated to begin construction in 2023, and aiming for a final production of around 5,600 tonnes of lithium content per year. King’s Mountain, North Carolina possesses hard rock (spodumene) lithium deposits with Piedmont Lithium estimating a production of lithium hydroxide to begin in 2026, expecting to produce 30,000 tonnes of lithium hydroxide per year when fully operational. The Salton Sea in California is home to several active geothermal plants with a complex mixed salt content, which is currently challenging and expensive to separate. Controlled Thermal Resources, operator of the proposed geothermal energy and lithium extraction pilot plant is hoping to develop up to 20,000 tonnes of lithium hydroxide per year by 2024.

[7] Helpful FAQ from the Nickel Institute regarding Life Cycle data regarding global nickel production and the 13 kg of CO2 emissions associated with 1 kg of Ni production.

[8] In-depth analysis of current critical mineral holdings within China by Brookings Institute.